This article started with only the benchmark part, because I was curious of the impact of some parameters of the API, and if I could make things go faster. One thing led to another, I was suddenly writing a lot of pieces around Avro, talking about different frameworks and several ways of doing things!

This article does not explains what is Avro (ie: a data serialization system) and what are the use-cases. The best source for this is the official website: Apache Avro.

We’ll just go quickly through the basics of the Avro API, then we’ll focus on:

- The Java Avro API performance with some jmh benchmarks.

- The schemas registry management.

- The schemas/case classes auto-generation in Scala.

Summary

The basics

First, let’s remember how to use the Avro Java API to deal with Schema, GenericRecord, and serialization/deserialization.

How to create an Avro Schema and some records

- Create a

Userschema with 80 columns:

val schema: Schema = {

val fa = SchemaBuilder.record("User").namespace("com.sderosiaux").fields()

(0 to 80).foldLeft(fa) { (fields, i) => fields.optionalString("value" + i) }

fa.endRecord()

}schema contains:

{"type":"record","name":"User","namespace":"com.sderosiaux","fields":[

{"name":"value0","type":["null","string"],"default":null},

{"name":"value1","type":["null","string"],"default":null},

...- Generate a record from this schema with random values:

val record = new GenericData.Record(schema)

(0 to 80).foreach(i => record.put("value" + i, math.random.toString))record contains:

{"value0": "0.09768197503406495", "value1": "0.5937827911773815", ... }We are going to use it to [read|write] [from|to] [input|output]streams or bytes during the benchmarks.

How to convert Avro records to bytes and vice-versa

To serialize a record (to be sent into Kafka for instance), we need a few pieces:

- A

GenericRecord(basically, this is a Map) we want to convert. - An

EncoderFactoryto provide an implementation oforg.apache.avro.io.Encoder(we’ll use bothBufferedBinaryEncoderandDirectBinaryEncoder, but aJsonEncoderalso exists). The encoder contains a bunch of low-level methods such aswriteFloat,writeStringand so on. It write them where it wants. The default Avro encoders write them only intoOutputStreams (in which you can only write bytes). - This is why we need to provide a

OutputStreamthat will be filled with bytes by theEncoder. Note: We can only write into aOutputStreamor convert it to bytes. - Because the

Encoderis low-level (writeFloat,writeString, one by one), we need a more high-level component to call the methodswrite*for us: it’s the role of theDatumWriterthat needs anEncoderto provide those atomic writes. TheDatumWriterjust knows how to parse (walk into) a complex object.

Here is the combinaison of those elements with a function that convert a complete record into bytes:

def toBytes(record: GenericRecord): Array[Byte] = {

val writer = new GenericDatumWriter[GenericRecord](schema.getSchema)

val out = new ByteArrayOutputStream()

val encoder = EncoderFactory.get().binaryEncoder(out, null)

writer.write(record, encoder)

encoder.flush() // !

out.toByteArray

}Same story to deserialize some bytes into a record (to be consumed by Kafka consumers for instance), except we use an InputStream and a Decoder (that can readInt, readString etc. from the stream):

def toRecord(buffer: Array[Byte], schema: Schema): GenericRecord = {

// We can provide 2 compatible schemas here: the writer schema and the reader schema

// For instance, the reader schema could be interested with only one column.

val reader = new GenericDatumReader[GenericRecord](schema)

val in = new ByteArrayInputStream(buffer)

val decoder = DecoderFactory.get().binaryDecoder(in, null)

reader.read(null, decoder)

}Don’t reuse those implementations, they are not optimized at all and create a whole stack of objects every time.

A same writer/reader can be used as many times as we want, as long as the data fits its schema.

Performances

We’ll do some benchmarks to see how many records/s we can encode/decode per second, and what are the differents combinaisons, to see if we can optimize something.

Here are the benchmarks conditions:

- CPU i5 2500k, 3.30GHz, 4 cores.

- jdk1.8.0_121

- sbt 0.13.8 and Scala 2.11.8

"org.apache.avro" % "avro" % "1.8.1""sbt-jmh" % "0.2.21"- JMH configured with: 1 iteration, 1 warmup iteration, 2 forks, 1 thread.

What we’ll test: encoders, decoders, reuse, bufferSize

We are going to test the default decoder binaryDecoder (buffered, it reads the bytes from the stream chunk by chunk) and its unbuffered version directBinaryDecoder (read on demand).

Same for the encoders binaryEncoder and directBinaryEncoder.

- Encoders and decoders accept a nullable

reuseparameter, to avoid to create new encoder/decoder instances in memory every time they write/read to/from a stream, and reuse (reconfigure) an existing one.

public BinaryEncoder binaryEncoder(OutputStream out, BinaryEncoder reuse) {}

public BinaryDecoder binaryDecoder(byte[] bytes, BinaryDecoder reuse) {}- There is an additional “reuse” parameter available when we deserialize a record: the

GenericDatumReader(which uses aDecoder) also accepts a nullablereuseargument to update an existing instance object instead of creating a new instance as result:

public D read(D reuse, Decoder in) throws IOException {}The class behind D must implement IndexedRecord to be reusable.

-

Finally, encoders and decoders also have a configurable

bufferSizeif applicable.- Default to 2048 bytes for the encoders: to bufferize serialized data before flushing them into the output stream.

- Default to 8192 bytes for the decoders: to read that much data from the input stream, chunk by chunk.

We are going to test all the “reuse” combinaisons and play with the size of the data to serialize/deserialize at once, and see the impact of the bufferSize.

binaryEncoderanddirectBinaryEncoder: with and without encoder reuse, with 1/10/1000 records.binaryDecoderanddirectBinaryDecoder: with and without decoder reuse, with and without record reuse, with 1/10/1000 records.

We will use a 80-Strings-containing-10-digits-each record as a fixture to serialize/deserialize.

Note that Strings are slower to handle than Doubles for instance. 80x-Doubles records offer ~20% more throughput than 80x-Strings records.

Benchmarks Results

Encoders

As previously said, we are going to test:

binaryEncoderanddirectBinaryEncoder: with and without encoder reuse, 1/10/1000 records.

This represents 12 tests (2*2*3), and they look like this (with JMH):

@Benchmark @Fork(2)

def withoutReuse1record(s: AvroState, bh: Blackhole) = {

s.encoder = s.encFactory.binaryEncoder(s.os, null)

writer.write(record, s.encoder)

bh.consume(s.os.toByteArray)

}

@Benchmark @Fork(2)

def withReuse1record(s: AvroState, bh: Blackhole) = {

s.encoder = s.encFactory.binaryEncoder(s.os, s.encoder)

writer.write(record, s.encoder)

bh.consume(s.os.toByteArray)

}The 10/1000 records tests just loop on the write line to write multiple records in the same iteration.

Here are the results:

> withoutReuse1record thrpt 40 80384,958 ± 208,405 ops/s

withReuse1record thrpt 40 3722,074 ± 174,148 ops/s

withoutReuse1recordDirect thrpt 40 3777,333 ± 175,610 ops/s

withReuse1recordDirect thrpt 40 3759,544 ± 172,830 ops/s

> withoutReuse10record thrpt 40 1190,944 ± 7,053 ops/s

withReuse10record thrpt 40 1085,234 ± 11,785 ops/s

withoutReuse10recordDirect thrpt 20 1096,232 ± 8,400 ops/s

withReuse10recordDirect thrpt 20 1097,405 ± 4,614 ops/s

> withoutReuse1000record thrpt 40 54,020 ± 0,359 ops/s

withReuse1000record thrpt 40 54,490 ± 0,292 ops/s

withoutReuse1000recordDirect thrpt 20 52,407 ± 0,383 ops/s

withReuse1000recordDirect thrpt 20 51,923 ± 0,280 ops/sThe bufferized and the direct encoders have the same performance, except for the 1 record processing without reuse withoutReuse1recordDirect where the direct encoder is losing off with withoutReuse1record.

If we look at the buffered encoder, without reuse, and normalize by records/s, we get:

- 1000 records: 54 ops/s, hence 54000 records/s.

- 10 records: 1190 ops/s, 11900 records/s.

- 1 record: 80384 record/s: the highest!

Writing multiple records did not improve our throughput because the buffer was still 2048 bytes. If we increase it to 1024*1024, we get much better results:

withoutReuse10record thrpt 20 5116,433 ± 30,456 ops/s

withoutReuse1000record thrpt 40 82,362 ± 0,238 ops/s- 10 records: 5116 ops/s, hence 51160 records/s.

- 1000 records: 82 ops/s, hence 82000 records/s, we achieve the best throughput here.

To conclude:

- The

directBinaryEncoderhas no buffer, and directly writes its data into the output stream. It’s only useful if no buffer is really needed (short live) or if the output stream is not compatible. - Do not use the

reuseparam for the encoders, it brings nothing performance wise. I should have check the memory usage. - It seems useless to batch the writes using the same encoder (poor gain) but if you do, increase greatly the

bufferSize.

Decoders

As previously said, we are going to test:

binaryDecoderanddirectBinaryDecoder: with and without decoder reuse, with and without record reuse, with 1/10/1000 records.

This represents 24 tests (2*2*\2*3) ! and they look like this:

@Benchmark

def withoutRecordwithoutReuse1(s: AvroState, bh: Blackhole) = {

s.decoder = s.decFactory.binaryDecoder(bytes, null)

bh.consume(reader.read(null, s.decoder))

}

@Benchmark

def withRecordwithoutReuse1(s: AvroState, bh: Blackhole) = {

s.decoder = s.decFactory.binaryDecoder(bytes, null)

bh.consume(reader.read(record, s.decoder))

}

...… with all the variations with/without, and with 1/10/1000 records tests using a simple loop, as with the Encoders benchmarks.

Here are the results:

withRecordwithReuse1 thrpt 20 185953,460 ± 1111,831 ops/s

withRecordwithoutReuse1 thrpt 20 187475,498 ± 979,138 ops/s

withoutRecordwithReuse1 thrpt 20 185662,697 ± 919,191 ops/s

withoutRecordwithoutReuse1 thrpt 20 187440,727 ± 966,958 ops/s

withRecordwithReuse10 thrpt 20 19025,723 ± 46,294 ops/s

withRecordwithoutReuse10 thrpt 20 19048,485 ± 54,986 ops/s

withoutRecordwithReuse10 thrpt 20 18506,429 ± 64,043 ops/s

withoutRecordwithoutReuse10 thrpt 20 18422,282 ± 62,241 ops/s

withRecordwithReuse1000 thrpt 20 190,376 ± 1,287 ops/s

withRecordwithoutReuse1000 thrpt 20 184,054 ± 2,828 ops/s

withoutRecordwithReuse1000 thrpt 20 188,073 ± 1,671 ops/s

withoutRecordwithoutReuse1000 thrpt 20 187,071 ± 0,922 ops/sI didn’t test the directBinaryDecoder, do you really want me to? ;)

We can see that reuse or not, multiple records or not, it’s the same performance (even with a bigger buffer)! Around 190k record/s, no matter how many records in a row.

To conclude:

- Do how you want when you deserialize the records, it does not matter, except on the memory and GC pressure probably: reusing encoders and records seems like a good idea.

Versioning the Avro schemas

When we use Avro, we must deal with a Schema Registry (shortcut: SR).

Why?

It’s useless to send the schema of the data along with the data each time (as we do with JSON). It’s not memory and network efficient. It’s smarter to just send an ID along the data that the other parties will use to understand how are encoded the data.

Moreover, this is necessary when applications talk to each other and are never shutdown at the same time (the data are going to evolve one day right?), or when we have a message broker (like Kafka) where the consumers are never stopped and should be able to read messages encoded with a new schema (a new column for instance, a renaming, a deleted column..). We just want to update the application that produces the messages, not necessarily all the consumers.

Last but not least, that gives us an idea of what’s in the pipes without checking the code, because the schemas are externalized into another storage, which is HTTP accessible, and it provides an audit (what changed, when..).

Confluent had written a nice article about them and why it’s mandatory.

There are two main schema registries out there:

- Confluent’s: integrated with the Confluent’s Platform.

- schema-repo which is the implementation of AVRO-1124.

Dealing with a SR enforces to code the version of the schema into the message, generally in the first bytes.

- On serialization: we contact the SR to register (if not already) the Avro schema of the data we’re going to write (to get a unique ID). We write this ID as the first bytes in the payload, then we append the data. A schema has a unique ID (so multiple messages use the same schema ID).

- On deserialization: we read the first bytes of the payload to know what is the version of the schema that was used to write the data. We contact the SR with this ID to grab the Schema if we don’t have it yet, then we parse it to a

org.apache.Schemaand we read the data using the Avro API and thisSchema(or we can read with another compatibleSchemaif we know it’s backward/forward compatible).

To resume, the serialization/deserialization of the data must now deal with another step for each and every message. Hopefully, the client API of the SR is always caching the requested schemas, to not call the SR server every time (HTTP API).

Subjects

We need to introduce the notion of Subject when we are using a SR.

A subject represents a collection of compatible (according to custom validation rules) schemas in the SR.

The versions we talked about are only unique per subject:

- a subject A can have v1, v2.

- a subject B can have v1, v2, v3.

With schema-repo

It’s not maintained anymore because it works perfectly! The repo: schema-repo.

It’s a simple HTTP service that can store and retrieve schemas on disk, in memory (for development purpose only), or in Zookeeper. We can download a jar with all dependencies, it just needs a simple configuration file to declare where to store the schemas.

schema-repo is not necessarily specialized for Avro Schemas. The “schemas” (which are simply the value of the key (subject, version)) can actually be anything we want (integers, strings, whatever), using Avro Schemas is only one of their usage.

$ cat sr.config

schema-repo.class=org.schemarepo.InMemoryRepository

schema-repo.cache=org.schemarepo.InMemoryCache

$ java -jar schema-repo-bundle-0.1.3-withdeps.jar sr.config

...

00:46:50 INFO [o.e.jetty.server.AbstractConnector] Started SelectChannelConnector@0.0.0.0:2876Let’s describe the available route to understand clearly its purpose:

-

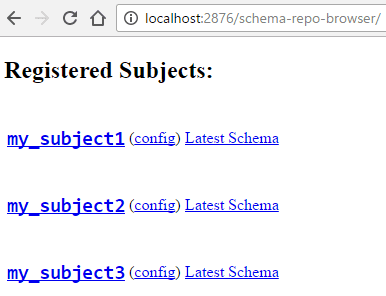

The Human Interface, to browse the subjects:

-

The JSON API (that will be used by the Java client API of schema-repo):

GET /schema-repo: list all the subjects.GET /schema-repo/{subject}: 200 if the subject exists.GET /schema-repo/{subject}/all: list all the (version+schema) of the subject.GET /schema-repo/{subject}/config: display the config of the subject.GET /schema-repo/{subject}/latest: get the latest schema of the subject.GET /schema-repo/{subject}/id/{id}: get a specific version of the subject.PUT /schema-repo/{subject}: create a new subjectPOST /schema-repo/{subject}/schema: check if the schema in this subject existsPUT /schema-repo/{subject}/register: add a schema to the subject. It can fail if the schema is not compatible with the previous one (according to the validator rules of the subject, if set).PUT /schema-repo/{subject}/register_if_latest/{latestId}: add a schema only if the given version was the latest.

It’s basically a Map[String, (Map[Int, Any], Config)] (!).

Note that there is now way to remove a schema from a subject, it’s immutable. It’s only possible by removing them manually from their storage.

-

The whole configuration of the schema registry:

Configuration of schema-repo server:

schema-repo.start-datetime: Wed Feb 22 00:46:50 CET 2017

schema-repo.class: org.schemarepo.InMemoryRepository

schema-repo.cache: org.schemarepo.InMemoryCache

schema-repo.validation.default.validators:

schema-repo.jetty.buffer.size: 16384

schema-repo.jetty.header.size: 16384

schema-repo.jetty.host:

schema-repo.jetty.port: 2876

schema-repo.jetty.stop-at-shutdown: true

schema-repo.jetty.graceful-shutdown: 3000

schema-repo.rest-client.return-none-on-exceptions: true

schema-repo.json.util-implementation: org.schemarepo.json.GsonJsonUtil

schema-repo.logging.route-jul-to-slf4j: true

schema-repo.zookeeper.ensemble:

schema-repo.zookeeper.session-timeout: 5000

schema-repo.zookeeper.connection-timeout: 2000

schema-repo.zookeeper.path-prefix: /schema-repo

schema-repo.zookeeper.curator.number-of-retries: 10

schema-repo.zookeeper.curator.sleep-time-between-retries: 2000Hopefully, there is a Java API to deal with all the endpoints.

Client API

The client API is really just a wrapper that contact the schema registry using Jersey client.

Here are the necessary sbt dependencies to add:

libraryDependencies += "org.schemarepo" % "schema-repo-client" % "0.1.3"

libraryDependencies += "org.slf4j" % "slf4j-simple" % "1.7.23"

libraryDependencies += "com.sun.jersey" % "jersey-client" % "1.19"

libraryDependencies += "com.sun.jersey" % "jersey-core" % "1.19"And here is a simple example where we create a new subject with 2 schemas:

val repo = new RESTRepositoryClient("http://localhost:2876/schema-repo", new GsonJsonUtil(), false)

// register create a new subject/schema or return the existing one if one matches

val subject = repo.register("toto-" + Math.random(), SubjectConfig.emptyConfig())

subject.register("SCHEMA A")

subject.register("SCHEMA B")

println(s"entries: ${subject.allEntries()}")

println(s"latest: ${subject.latest()}")Output:

[main] INFO org.schemarepo.client.RESTRepositoryClient -

Pointing to schema-repo server at http://localhost:2876/schema-repo

[main] INFO org.schemarepo.client.RESTRepositoryClient -

Remote exceptions from GET requests will be propagated to the caller

entries: [1 SCHEMA B, 0 SCHEMA A]

latest: 1 SCHEMA BSubject wrappers: read-only, cache, validating

schema-repo provides 3 Subject wrappers:

- A read-only subject, to pass it down safely:

// wrap the subject into a read-only container to ensure nothing can register schemas on it

val readOnlySubject = Subject.readOnly(subject)

// readOnlySubject.register("I WILL CRASH")- A cached subject, to avoid doing HTTP requests:

// cache the schemas id+value in memory the first time they are accessed through the subject.

// This is to avoid contacting the HTTP schema registry if it was already seen.

val cachedSubject = Subject.cacheWith(subject, new InMemorySchemaEntryCache())

val schemaC = cachedSubject.register("SCHEMA C") // HTTP call, creating ID "2"

// ...

val schemaC = cachedSubject.lookupById("2") // No HTTP call, it was in the cache- A validating subject, to ensure a compatibility with the existing schemas of the subject. For instance, we can forbid the new schema to be shorter than the existing ones (?!):

// wrap the subject with the default validators

val alwaysLongerValidator = new ValidatorFactory.Builder()

.setValidator("my custom validator", new Validator {

override def validate(schemaToValidate: String, schemasInOrder: Iterable[SchemaEntry]): Unit = {

if (!schemasInOrder.asScala.forall(_.getSchema.length <= schemaToValidate.length)) {

throw new SchemaValidationException("A new schema can't be shorter than the existing ones")

}

}

})

.setDefaultValidator("my custom validator")

.build()

val validatingSubject = Subject.validatingSubject(subject, alwaysLongerValidator)

validatingSubject.register("SCHEMA 4")

validatingSubject.register("SHORT") // Exception !Let’s use this validator thing to do something truly useful in our case..

Ensure Avro schemas full compatibility

We can ensure that any new Avro schema is compatible (forward and backward) with all the existing Avro schemas of a subject:

val avroValidators = new ValidatorFactory.Builder()

.setValidator("avro full compatibility validator", new Validator {

override def validate(schemaToValidate: String, schemasInOrder: Iterable[SchemaEntry]): Unit = {

// We must NOT use the same Parser because a Parser stores which schema it has already parsed

// and throw an exception if we try to parse 2 schema with the same namespace/name

val writerSchema = new Schema.Parser().parse(schemaToValidate)

schemasInOrder.asScala

.map(s => new Schema.Parser().parse(s.getSchema))

.map(s => SchemaCompatibility.checkReaderWriterCompatibility(s, writerSchema))

.find(_.getType == SchemaCompatibilityType.INCOMPATIBLE)

.foreach(incompat => throw new SchemaValidationException(incompat.getDescription))

}

})

// The subject can set which validator to use in its config.

// The default validators are used if they are not defined explicitely.

.setDefaultValidator("avro full compatibility validator")

.build()It means that we ensure any event written with the new schema can be read by the existing schemas, AND, that the new schema can read the events written by any existing schemas.

Here is an example where we try at the end to insert an incompatible schema:

It’s incompatible because we removed a field: the old schemas are not compatible anymore. If an app was still reading events using the original schema, it wouldn’t be able to deserialize the new events because it expects a first property (no default value).

// we can specify which validator to use, and not rely on the default validators of the factory

val config = new SubjectConfig.Builder().addValidator("avro full compatibility validator").build()

val avroSubject = Subject.validatingSubject(

client.register("avro-" + Math.random(), config),

avroValidators)

println(avroSubject.register("""

|{

| "type": "record",

| "namespace": "com.example",

| "name": "Person",

| "fields": [

| { "name": "first", "type": "string" }

| ]

|}

""".stripMargin)) // OK!

println(avroSubject.register("""

|{

| "type": "record",

| "namespace": "com.example",

| "name": "Person",

| "fields": [

| { "name": "first", "type": "string" },

| { "name": "last", "type": "string" }

| ]

|}

""".stripMargin)) // OK!

println(avroSubject.register("""

|{

| "type": "record",

| "namespace": "com.example",

| "name": "Person",

| "fields": [

| { "name": "last", "type": "string" }

| ]

|}

""".stripMargin)) // INCOMPATIBLE, WILL FAIL!Output:

0 { "type": "record", ... }

1 { "type": "record", ... }

Exception in thread "main" org.schemarepo.SchemaValidationException:

Data encoded using writer schema:

{

"type" : "record",

"name" : "Person",

"namespace" : "com.example",

"fields" : [ {

"name" : "last",

"type" : "string"

} ]

}

will or may fail to decode using reader schema:

{

"type" : "record",

"name" : "Person",

"namespace" : "com.example",

"fields" : [ {

"name" : "first",

"type" : "string"

}, {

"name" : "last",

"type" : "string"

} ]

}In a company, it’s quite straightforward to create a small custom framework around those pieces to ensure any application pointing to the same schema repository won’t break rules and inject bad Avro schemas.

With Confluent’s Schema Registry

The schema registry of Confluent is part of a much much bigger platform and is tightly linked to Kafka, using it as a storage. It’s way more maintained than schema-repo as you can see on Github: confluentinc/schema-registry. It is dedicated to Avro schemas and nothing else.

The platform with its schema registry is downloable here on Confluent’s website: confluent-oss-3.1.2-2.11.zip.

Let’s go into the wild and try to start the schema registry. We first need to start Zookeeper and Kafka. The schema registry depends on Zookeeper and looks for Kafka brokers. If it can’t find one, it won’t start.

The Confluent platform provides some default config files we can use to start the whole stack:

$ cd confluent-3.1.2

$ ./bin/zookeeper-server-start -daemon ./etc/kafka/zookeeper.properties

$ ./bin/kafka-server-start -daemon ./etc/kafka/server.properties

$ ./bin/schema-registry-start ./etc/schema-registry/schema-registry.properties

[2017-02-24 00:01:47,667] INFO SchemaRegistryConfig values:

...

kafkastore.topic = _schemas

metrics.jmx.prefix = kafka.schema.registry

schema.registry.zk.namespace = schema_registry

avro.compatibility.level = backward

port = 8081

...

[2017-02-24 00:01:53,858] INFO Started @7282ms (org.eclipse.jetty.server.Server:379)

[2017-02-24 00:01:53,860] INFO Server started, listening for requests...There are also some official Docker images available.

I’ve kept only the interesting parts of the config:

- It stores the schemas modifications into a kafka topic

_schemas. - We can use JMX to check the internals of the registry.

- In Zookeeper, we’ll find the data in

/schema_registry. - We can only insert backward compatible Avro schemas (in the subject) and it’s configurable.

We can check in Zookeeper its state:

$ ./bin/zookeeper-shell localhost

> ls /schema_registry

[schema_registry_master, schema_id_counter]

> get /schema_registry/schema_registry_master

{"host":"00-666-99.eu","port":8081,"master_eligibility":true,"version":1}The schema registry is using Zookeeper to coordinate with another schema registries (master writer/slave readers) to ensure scaling, HA and unique global IDs. It also listens to Kafka to load up the data on startup, and write updates into it (the master): this is why those elements are mandatory.

Let’s do like with schema-repo and list the useful routes:

GET/PUT /config: retrieve/set the global Avro compabitility levelGET/PUT /config/{subject}: retrieve/set this subject Avro compabitility levelGET /subjects: list all the subjectsPOST /subjects/{subject}: check if a schema belongs to a subjectGET /subjects/{subject}/versions: list all the schemas of this subjectGET /subjects/{subject}/versions/{version}: retrieve this schema version of this subjectPOST /subjects/{subject}/versions: register a new schema for this subjectGET /schemas/ids/{id}: get the schema with this ID (globally unique).POST /compatibility/subjects/{subject}/versions/{version}: Test if the given schema (in the payload) is compatible with the given version.

All the POST/PUT must send the header: Content-Type: application/vnd.schemaregistry.v1+json to be taken into account.

{version}starts at 1 or can be “latest”.- In this schema registry, the ID is globally unique per distinct schema. We don’t need the subject and the version to retrieve a schema, we just need its ID.

If we register some subjects and schemas, we can see all our changes in Kafka:

$ ./bin/kafka-console-consumer --bootstrap-server localhost:9092 --topic _schemas \

--from-beginning --property print.key=true

{"magic":0,"keytype":"NOOP"} null

{"subject":"subject_test","version":1,"magic":0,"keytype":"SCHEMA"} {"subject":"subject_test","version":1,"id":21,"schema":"\"string\""}

{"subject":"subject_test2","version":1,"magic":0,"keytype":"SCHEMA"} {"subject":"subject_test2","version":1,"id":21,"schema":"\"string\""}

...Hopefully, we have also a Java Client API to deal with it.

Client API

Here are the sbt changes and a small application to play with the client API:

resolvers += "Confluent" at "http://packages.confluent.io/maven"

libraryDependencies += "io.confluent" % "kafka-schema-registry-client" % "3.1.2"val client = new CachedSchemaRegistryClient("http://vps:8081", Int.MaxValue)

val s1 = SchemaBuilder.builder("com.sderosiaux").record("Transaction").fields()

.requiredString("uuid").endRecord()

val s2 = SchemaBuilder.builder("com.sderosiaux").record("Transaction").fields()

.requiredString("uuid")

.optionalDouble("value")

.endRecord()

val id1 = client.register("MY_SUBJECT", s1)

val id2 = client.register("MY_SUBJECT", s2)

println(id1, id2)

//(41,42)

val metadata = client.getLatestSchemaMetadata("MY_SUBJECT")

println(s"latest: ${metadata.getSchema}")

// latest: {"type":"record","name":"Transaction","namespace":"com.sderosiaux","fields":[...]}

// helper methods:

println("fully compatible? " + AvroCompatibilityChecker.FULL_CHECKER.isCompatible(s1, s2))

// fully compatible? trueBy default, the client caches the schemas passing by to avoid querying the HTTP endpoint each time.

And that’s it, nothing more is provided. The schema validation is done on the schema registry itself according to its configuration (none, backward, forward, full). There is no custom configuration as with schema-repo, because it’s only Avro-based.

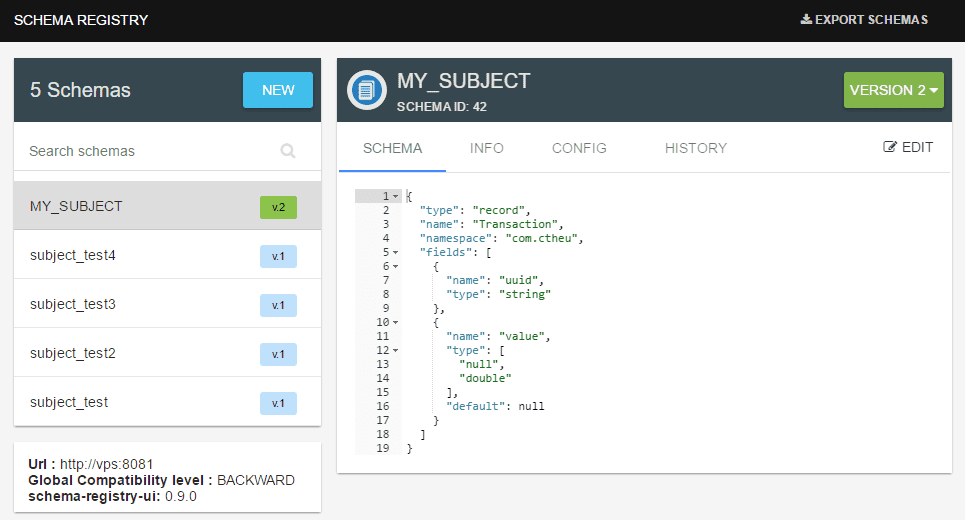

With a nice UI

There is an unofficial UI to go along with it: Landoop/schema-registry-ui.

We’ll need to enable CORS on the Schema Registry server of allow cross-domain requests if needed:

$ cat >> etc/schema-registry/schema-registry.properties << EOF

access.control.allow.methods=GET,POST,PUT,OPTIONS

access.control.allow.origin=*

EOFThen we can simply run a Docker image to get the UI working:

$ docker run -d -p 8000:8000 -e "SCHEMAREGISTRY_URL=http://vps:8081" landoop/schema-registry-uiWe have a nice UI to create/update schemas, access the configuration and so on. Much more practical than plain REST routes.

Encoding/decoding the messages with the schema ID

When we serialize/deserialize our data, we need to adjust to payload to write/read the schema id: the consumers must know how to read the data, what is the format.

There is no standard around this, we can encode the data as we want, if we manage both sides (producer/consumer). But it’s quite classic to encode the same way as Confluent does, because at least, we know what to expect, and it’s quite popular.

Details on this page: http://docs.confluent.io/3.1.2/schema-registry/docs/serializer-formatter.html

Basically, the raw protocol is:

| Bytes | Contains | Desc |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Magic Byte | Confluent serialization format version number; currently always 0. |

| 1-4 | Schema ID | 4-byte schema ID as returned by the Schema Registry |

| 5-… | Data | Avro serialized data in Avro’s binary encoding. The only exception is raw bytes, which will be written directly without any special Avro encoding. |

If we would write some Scala code corresponding to this encoding, we can take back our example at the beginning of this article and adapt it fairly easily to write the header of each message:

val MAGIC_BYTE: Byte = 0x0

def toBytes(/* new */ schemaId: Int, record: GenericRecord): Array[Byte] = {

val writer = new GenericDatumWriter[GenericRecord](record.getSchema)

val out = new ByteArrayOutputStream()

/* new */ out.write(MAGIC_BYTE)

/* new */ out.write(ByteBuffer.allocate(4).putInt(schemaId).array())

val encoder = EncoderFactory.get().binaryEncoder(out, null)

writer.write(record, encoder)

encoder.flush()

out.toByteArray

}We should pass a subject and register the schema here instead of directly passing a schemaId, to save the new schemas transparently.

It’s along the line of the Confluent’s Avro Serializer that we can use in our Kafka Producer config, which will take care of doing this transparently:

props.put("schema.registry.url", url)

props.put("key.serializer", "io.confluent.kafka.serializers.KafkaAvroSerializer")

props.put("value.serializer", "io.confluent.kafka.serializers.KafkaAvroSerializer")Then, to read this payload, we need a little more work, because here, we must check the schema registry to get the schema back:

def toRecord(buffer: Array[Byte], registry: SchemaRegistryClient): GenericRecord = {

val bb = ByteBuffer.wrap(buffer)

bb.get() // consume MAGIC_BYTE

val schemaId = bb.getInt // consume schemaId

val schema = registry.getByID(schemaId) // consult the Schema Registry

val reader = new GenericDatumReader[GenericRecord](schema)

val decoder = DecoderFactory.get().binaryDecoder(buffer, bb.position(), bb.remaining(), null)

reader.read(null, decoder)

}The Confluent’s deserializer KafkaAvroDeserializer contains a bit more checks and logic such as the ability to provide another reader schema (ie: different of the one found in the payload, but still compatible), dealing with registry subject names (for Kafka messages key and value), and it can use Avro SpecificData (ie: not only GenericData).

In the Confluent’s way, we would configure our Kafka Consumer properties with:

props.put("schema.registry.url", url);

props.put("key.deserializer", "io.confluent.kafka.serializers.KafkaAvroDeserializer")

props.put("value.deserializer", "io.confluent.kafka.serializers.KafkaAvroDeserializer")Generate schemas or case classes automatically

Finally, because we don’t want to write the Avro schema ourself, OR, we don’t want to write the corresponding case classes ourself (to avoid typos and maintenance), we can use schema or case class generators.

Here are 2 nice projects along this way:

- avro4s: both ways: Avro schema ⇔ case class + serialization/deserialization.

- avrohugger: Avro schema to case class only.

Both ways are valid. Generating the case classes from the schemas is more powerful and customizable because we can write the schemas with the full power of the Avro spec and generate the case classes from them whereas the inverse is more complex to handle in the code.

edit 2018-01-07: A new comer: formulation, more expressive, no macros, shapeless based, also integrated with refined (constraints on types).

avro4s

libraryDependencies += "com.sksamuel.avro4s" %% "avro4s-core" % "1.6.4"avro4s can:

- generate the Avro schema from any case class.

- handle serialization/deserialization of case classes to Avro raw data (using the Avro encoders).

It also comes with an sbt plugin sbt-avro4s that can generate case classes from existing Avro schemas. There are some limitations, like with nested generics, cycle references, but it works flawlessly for most cases.

Generate a schema from a case class

Scala macros to the rescue:

import com.sksamuel.avro4s.AvroSchema

case class User(firstName: String, lastName: String, age: Int)

val schema: Schema = AvroSchema[User]

println(schema)Output:

{"type":"record","name":"User","namespace":"com.sderosiaux",

"fields":[{"name":"firstName","type":"string"},...] }avro4s handles most Scala -> Avro types conversion: all the basic types and specials such as: trait to enum or union, map, option or either to union.

Generate a case class from a schema

As we said, it’s also possible to do the reverse transformation using sbt-avro4s, ie: generate the case class from a schema.

In project/plugins.sbt:

addSbtPlugin("com.sksamuel.avro4s" % "sbt-avro4s" % "1.0.0")In src/main/resources/avro/Usr.avsc (AVro SChema, using a JSON notation):

{

"type":"record",

"name":"Usr",

"namespace":"com.sderosiaux",

"fields":[

{"name":"firstName","type":"string"},

{"name":"lastName","type":"string"},

{"name":"age","type":"int"}

]

}A dependent task will be associated to sbt compile but it’s also possible to call this task directly to run the generation:

avro2Class

[info] [sbt-avro4s] Generating sources from [src\main\resources\avro]

[info] --------------------------------------------------------------

[info] [sbt-avro4s] Found 1 schemas

[info] [sbt-avro4s] Generated 1 classes

[info] [sbt-avro4s] Wrote class files to [target\scala-2.11\src_managed\main\avro]The Usr case class is generated in target\scala-2.11\src_managed\main\avro.

We can use it:

val u = Usr("john", "doe", 66)There is even an online generator doing exactly this: http://avro4s-ui.landoop.com/.

Serialization and deserialization in a nutshell

// NO schema written. Uses Avro binaryEncoder.

// Useful when combined to a Schema Registry that provides an ID instead.

val bin = AvroOutputStream.binary[User](System.out)

// Schema written. Uses Avro jsonEncoder.

val json = AvroOutputStream.json[User](System.out)

// Schema written. Store the schema first, then the records.

val data = AvroOutputStream.data[User](System.out)

val u = Seq(User("john", "doe", 66), User("mac", "king", 24))

json.write(u)

bin.write(u)

data.write(u)

val bytes: Array[Byte] = ???

AvroInputStream.binary[User](bytes).iterator.foreach(println)

AvroInputStream.json[User](bytes).iterator.foreach(println)

AvroInputStream.data[User](bytes).iterator.foreach(println)It’s also possible to work with GenericRecord directly:

val u = User("john", "doe", 66)

val genericRecord = RecordFormat[User].to(u)

val u2 = RecordFormat[User].from(genericRecord)

assert(u == u2)There are a few more features available, take a peek at the README (type precision, custom mapping).

avrohugger

Avrohugger does not rely on macros but on treehugger, which generates scala source code directly (whereas macros evaluation is just another phase in the compiler processing).

Avrohugger is a set of libraries and tools:

"com.julianpeeters" %% "avrohugger-core" % "0.15.0": generate Scala source code from Avro schemas. It can generates case classes but alsoSpecificRecordBaseclasses andscavrocase classes (scavro is another library to generate case classes from schemas).

import avrohugger._

val schema: Schema = ???

println(new Generator(format.Standard).schemaToStrings(schema))

// case class Usr(firstName: String, lastName: String, age: Int)

println(new Generator(format.SpecificRecord).schemaToStrings(schema))

// case class Usr(var firstName: String, var lastName: String, var age: Int)

// extends org.apache.avro.specific.SpecificRecordBase { ... }

println(new Generator(format.Scavro).schemaToStrings(schema))

// case class Usr(firstName: String, lastName: String, age: Int)

// extends org.oedura.scavro.AvroSerializeable { ... }

// More useful, it can generate to files directly:

new Generator(format.Standard).schemaToFile(schema /*, outDir = "target/generated-sources"*/)It handles properly Scala enums and has some options to map the generated case classes:

val schema = new Schema.Parser().parse(

"""

|{

| "type":"record",

| "name":"Usr",

| "namespace":"com.sderosiaux",

| "fields":[

| {"name":"firstName","type":"string"},

| {"name":"lastName","type":"string"},

| {"name":"age","type":"int"},

| {"name": "suit", "type": { "name": "Suit", "type": "enum",

| "symbols" : ["SPADES", "HEARTS", "DIAMONDS", "CLUBS"] } }

| ]

|}

""".stripMargin)

println(new Generator(format.Standard,

avroScalaCustomTypes = Map("int" -> classOf[Double]),

avroScalaCustomNamespace = Map("com.sderosiaux" -> "com.toto"),

avroScalaCustomEnumStyle = Map(),

restrictedFieldNumber = false

).schemaToStrings(schema))Cleaned output:

object Suit extends Enumeration {

type Suit = Value

val SPADES, HEARTS, DIAMONDS, CLUBS = Value

}

case class Usr(firstName: String, lastName: String, age: Double, suit: Suit.Value)- sbt-avro-hugger

addSbtPlugin("com.julianpeeters" % "sbt-avrohugger" % "0.15.0"): a plugin just to automatize these generations using sbt tasks. - avro-scala-macro-annotations

"com.julianpeeters" % "avro-scala-macro-annotations_2.11" % "0.11.1": fills an existing emptycase classat compilation time, with the fields found in an avro schema or in an avro data file, eg:

// From a schema:

@AvroTypeProvider("avro/user.avsc")

case class User()

// => case class User(firstName: String, age: Int)

// OR from the data:

@AvroTypeProvider("avro/user.avro")

case class User()

// => case class User(firstName: String, age: Int)Conclusion

It’s time to forget about JSON (we already forgot about XML). It’s nice for humans because it’s verbose and readable, but it’s not efficient to work with. We repeat the schema of the data in all messages, we can make typos and send crap over the wires..

Avro fixes those issues:

- Space and network efficience thanks to a reduced payload.

- Schema evolution intelligence and compatibility enforcing.

- Schema registry visibility, centralization, and reutilisation.

- Kafka and Hadoop compliant.

Note that it exists a lot of other communication protocol such as: MessagePack, Thrift, Protobuf, FlatBuffers, SBE, Cap’n Proto. Most of them supports schemas, some are much more efficient (zero-copy protocols), other are more human friendly, all depends on the needs.