This is a cross-post from my Medium if you prefer.

We all started with Scala Futures. They bring so much power and their syntax is simple enough. “Concurrency and asynchrony made easy” could be their tagline.

Futures allow us to deal with “values that don’t exist yet”. We can create a pipeline of transformations on top that will be applied when the time comes: when the Future will be fulfilled.

We can execute Futures in parallel, we can also race them. As developers, we often need to deal with concurrent operations. We have several databases, several services: we always wait for some answers asynchronously.

This sort of code does not —should not— exist anymore, RPC-calls-looking-like-local-calls (RMI, CORBA, EJB) are gone:

val result: User = DB.Users.byId(42)It should be gone, for the simple reason that it’s not possible to get the result instantly from a database or a service: the network is in-between, and the network is unreliable. It should be wrapped into some form of asynchronous effect, such as Future or even better: F[_].

Wrapping something into a Future or an asynchronous effect does not mean the code inside is asynchronous: JDBC is still synchronous and will still block its thread. Maybe JDBC-Next will be out some day.

Summary

- Presence in the Scala Ecosystem

- From Future to the future

- Referential Transparency

- Accidental Sequentiality & Consistent Execution

- Memoization is a two-edged sword

- ExecutionContext is like a cockroach

- No Traverse typeclass instance

- Performance

- Conclusion

Presence in the Scala Ecosystem

A lot of well-known Scala frameworks and libraries rely on Futures. Futures are part of the official Scala Library: it’s easy to work with and do not sound exotic to newcomers. No need to import any 3rd party library.

Akka is using Scala Futures all over the place. The ask operator ? returns a Future. akka.pattern.* uses Futures (after to define a timeout to some computations). pipeTo only listens to a Future to send its value to an actor. Same story in Akka Streams: mapAsync only accepts Futures.

Play Framework —based on Akka— also uses Futures where asynchrony is needed: the routes handlers can either be synchronous or return a Future (the ActionBuilder).

Apache Spark uses Futures to deal with async operations on RDDs (collectAsync, countAsync etc.), and with its internal RPC system.

From Future to the future

As you remember, once upon a time, all our repositories were typed like this:

trait ItemsRepository {

def getById(id: Int): Future[Option[Item]]

def save(item: Item): Future[Unit]

}Soon, Future was not enough anymore. We started to use alternatives, such as Scalaz Task, Monix Task, cats-effect IO or typeclasses such as Sync[F].

Why is that?

- What do they offer that Futures can’t?

- What do they don’t offer that Futures force us to deal with?

Referential Transparency

As we saw in my previous post, Referential Transparency is a good way to write a robust program. It makes it easy to reason about, and resilient to refactoring mistakes.

Futures are clearly not referentially transparent because they are eager or strict (inverse of lazy), and they memoize their value.

Just typing this dead code (not used after) creates a side-effect (output):

Future(println("hello"))If the codeblock inside throws an exception, nothing happens, the error is “gone” (because we didn’t “subscribed” to it).

If we use its reference several times:

val f = Future(println("hello"))

Future.sequence(List(f, f, f, f))We only get one side-effect (one “hello”) because it’s the same Future, and Futures memoize their result. Therefore, the computation is done only once.

This clearly goes against referential transparency because if we replace f by its value, we’ll get 4 side-effects (as you expect when reading the code here):

Future.sequence(List(Future(println("hello")), Future(println("hello")),

Future(println("hello")), Future(println("hello"))))“Yeah but it’s stupid, that will never happen to me”. It will happen when you’re going to inline or factor-out some piece of code. With referentially transparent code, you don’t have to think about it: it will just work as expected, the behavior won’t change for sure. Playing with Future is playing with fire.

A Future doesn’t describe an execution, it executes.

Accidental Sequentiality & Consistent Execution

Who never did the following mistake?

def getUser(id: Int): Future[User] = ???

def getAds(): Future[List[Ad]] = ???

for {

user <- getUser(5)

ads <- getAds()

bestAds <- findBestAdsForUser(user, ads)

} yield bestAdsOur computation is sequential (getAds() being executed in the flatMap of getUser(5)) but getUser(5) and getAds() should be concurrent: they don’t rely on each other, they are independent.

We have 2 solutions, either start them (at least the second one) beforehands:

val allAds = getAds() // the Future starts here

for {

user <- user

ads <- allAds // will rely on memoization

bestAds <- findBestAdsForUser(user, ads)

} yield bestAdsOr we clearly state the intent that both are independent (better) thanks to Future’s Applicative (provided by cats):

(getUser(5), getAds()).mapN(findBestAdsForUser)With Task (or IO), the intermediate solution wouldn’t fix our issue (create the Task before), because it’s just declarative (lazy), the computation would not start beforehands. We would need to make our explicit our concurrency, and use the latter form (the Applicative’s).

With Futures, our code acts differently according to where we write our code. We should not expect this behavior.

It’s not something Futures “fix” for us, it’s more something (the concurrency) we should be explicit about. We need to understand how our program works, and have an execution consistent to the code written.

Memoization is a two-edged sword

As we saw, Future memoizes its result. You can ask its result a thousand times, it will always return the same result, cached in its internals.

It can be super useful to cache some HTTP results for instance. You know you can dispatch the same Future here and there, only one call will be made and everything will share its result.

Unfortunately, it’s also a downside and make it non-functional according to the referential transparency:

val f = Future(println("hello"))

Await.result(f, Duration.Inf)

Await.result(f, Duration.Inf)This will only print “hello” once. The Future being eager, the computation and side-effect has already been evaluated on the first line. Waiting for its result 0 or N times doesn’t change a thing even if the code “looks like” it will do the execution several times.

When you don’t want memoization, you have no choice, you must create a new reference to cause a new execution. If you have already a reference (to a Task or IO), you can re-execute as many times as you want to provide a new computation (imagine a call to a service that gives the time).

Note that Monix Task provides a way to memoize its result: it’s explicit to the reader and more granular. We can memoize only on successes, to retry on failures.

ExecutionContext is like a cockroach

We can’t talk about Futures without talking about its ExecutionContext: they form a duo (unfortunately).

A Future and most of its functions (map, flatMap, onComplete) must know where to execute, on which thread: this is what an ExecutionContext provides.

Each time we add a transformation or a callback, we must provide an ExecutionContext, it’s part of the implicits:

def onComplete[U](f: Try[T] => U)(implicit executor: ExecutionContext): Unit

def foreach[U](f: T => U)(implicit executor: ExecutionContext): Unit

def map[S](f: T => S)(implicit executor: ExecutionContext): Future[S]

def flatMap[S](f: T => Future[S])(implicit executor: ExecutionContext): Future[S]If you have a polymorphic trait based on F[_] (à la tagless final), you can’t obviously add (implicit ec: ExecutionContext) to all your methods. F[_] is abstract and can be something else than Future, which wouldn’t need any ExecutionContext. Therefore, the implementation would need to add it in its constructor but it’s not a good choice —and no, we must no rely on the global ExecutionContext.

It means the ExecutionContext was decided early on (generally on startup) and therefore is fixed. But callers should be able to decide on which ExecutionContext they want to run your function (like using their own). It’s not the responsability of the callee service to enforce it (exceptions aside).

Moreover, with Futures, you must add this (implicit ec: ExecutionContext) everywhere. It propagates into all your codebase because you must follow the functions path: a() calls b() calls c() which needs an ExecutionContext? So you need to add the implicits to a() and b()! How great is not that?

Task and its friends doesn’t need this because they don’t execute anything right away. The ExecutionContext or Scheduler is only provided at the “end of the world” when the program really starts the executions — exception aside when you want to run a computation in a specific context like with executeOn.

It means your functions don’t have to pass any implicit, and your abstractions can stay abstract without any ExecutionContext dependency.

No Traverse typeclass instance

Future.sequence and Future.traverse —equivalent of .map + .sequence— are also functions provided in cats by the Traverse typeclass. Task and IO both have an instance of Traverse.

Edit: This last statement was just wrong. Traverse is not available for IO nor Task. Task provides a custom .sequence() and IO provides none of them. You can disregard the rest of this paragraph. It was late for me. :-)

Traverse also provides more generic methods to avoid typing complex chunks of code which could introduce bugs, such as flatTraverse or traverseWithIndexM, and also exposes all the features from its parents: Functor and Foldable typeclasses (fold*, reduce*, partitionEither, and way more).

But because of the Futures peculiarities, it’s not possible to provide a Traverse instance for Future.

You can’t reuse your knowledge provided by these typeclasses —they apply on many things beside asynchronous computations, such as List— and you can’t make your program dependent on those typeclasses while relying on Future, because there is no such instance!

Cancellation

Racing computations

When we race Futures, the losers are not cancelled.

It means the processing (.map, .flatMap) is still going on even when the fastest Future already won, and the result is going to be discarded anyway. The “pipeline” of transformations will get to its end, because there is no such thing as cancellation with Futures — with Twitter’s Futures, there is something called Future Interrupts but it’s really not the same semantic.

Let’s see a Future race in action:

def waitFor(d: Duration): Future[Duration] =

Future(Thread.sleep(d.toMillis))

.map(_ => { println(s"in map: $d"); d })

val f = Future.firstCompletedOf(List(

waitFor(1.second),

waitFor(2.second))

)

val x = Await.result(f, Duration.Inf)

println(s"done in $x")This will print:

in map: 1 second

done in 1 second

in map: 2 secondsJust replace the println in the map with a webservice or database call, with a reading operation on a file or anything, and you understand why cancellation matters: you don’t want to process things for nothing.

It’s a common pattern to race several things to only keep the earliest, like a timeout exception, or to provide a fallback.

With Monix Task or cats-effect IO, we have the possibility to short-circuit the executions thanks to cancellation:

// The code is different from the previous one; it's more idiomatic to cats-effect

def waitFor[F[_]](d: FiniteDuration)

(implicit T: Timer[F], S: Sync[F]): F[Duration] = {

for {

_ <- T.sleep(d)

x <- S.delay { println(s"in flatMap: $d"); d }

} yield x

}

val t = IO.race(waitFor[IO](1.second), waitFor[IO](2.second))

val y = t.unsafeRunSync

println(s"done in $y")This will print:

in flatMap: 1 second

done in Left(1 second)The second execution has not finished: the sleep was cancelled.

Cancellation occurs for each cancellation boundary which can be set between flatMaps with IO.cancelBoundary or by using IO.cancelable to define a custom cancellable IO.

Cancellation needs to know what to do if it’s triggered, it’s not just some throw new CancelException, it’s smarter than this, and we have to write this code (like set a Boolean to False, or cancel some thread scheduling).

Stop on error

Cancellation is not only useful when we are racing computations. It’s also important to deal with errors when we process async executions in parallel. We generally want to stop and deal with the error, stopping the other executions and discarding their results such as demonstrated here:

def crash: Future[Duration] = Future.failed(new Exception("boom"))

val f = Future.sequence(List(crash, waitFor(1.second)))

val x = Try(Await.result(f, Duration.Inf))

println(s"result: $x")This will print:

result: Failure(java.lang.Exception: boom)

in map: 1 secondThe second Future was executed despite the first one crashing instantly.

If we do this with IO, the result is different:

def crash[F[_]](implicit F: Sync[F]): F[Duration] =

F.raiseError(new Exception("boom"))

val t = IO.race(crash2[IO], waitFor2[IO](1.second))

val y = t.attempt.unsafeRunSync

println(s"done in $y")This will print:

done in Left(java.lang.Exception: boom)Again, the second IO was cancelled.

We see that the IO/Task models are smarter thanks to their cancellation logic. It leads to avoid uncessary processing, which can result is less CPU/Network/Memory used, according to the prevented computations.

Viktor Klang provided a solution for Future’s cancellation relying on Thread’s interruptions.

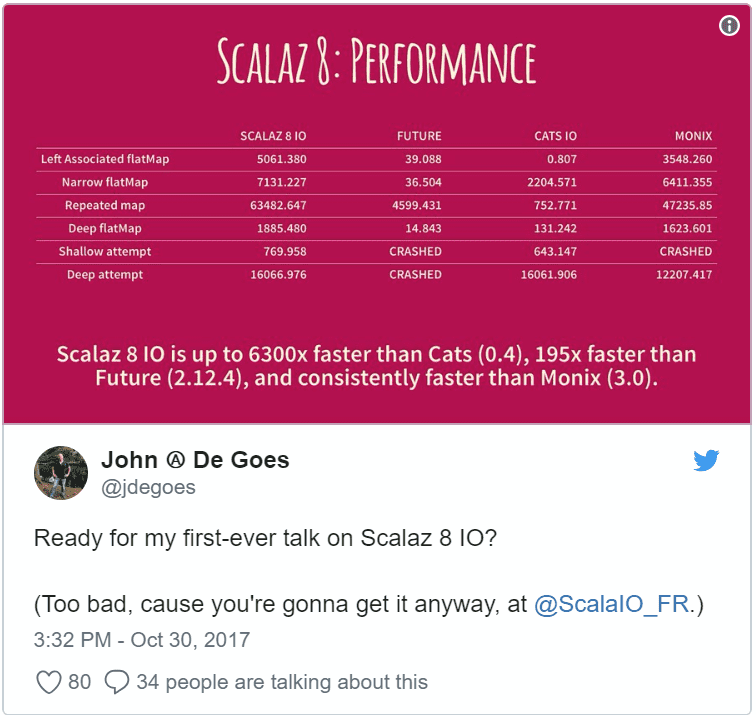

Performance

If performance matters, then the following tweet says it all.

I didn’t found any recent benchmark (it’s almost been a year since this tweet! cats was 0.4, it’s 1.2 now!) and didn’t try myself (booo).

If you have a recent version, feel free to share it, I’ll update this section accordingly.

I’ll just put this here for speculations:

Conclusion

Scala Futures were a very really good trampoline to highest standards provided by 3rd party libraries such as scalaz, cats, and monix.

Still, Futures improved over time (tons of optimizations in 2.12) but they can’t just break their model (and probably do no wish to).

A part of the Scala community seems to stray to the pure functional programming paradigm — with the rise of scalaz-zio, cats, monix, and advanced patterns based on typeclasses. It means Future can’t be of any help here, and this is where Task and IOs shine.

Thanks for all the fish.